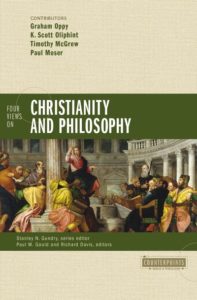

Learn more about the Four Views on Christianity and Philosophy (Zondervan, 2016) by going to the EPS book page.

I am a metaphysical naturalist: I hold a metaphysical naturalist worldview. I think that my metaphysical naturalist worldview is superior to competing Christian worldviews. In particular, I think that my metaphysical naturalist worldview commits me to less, but nowhere issues in weaker explanations, than competing Christian worldviews.

I am a philosophical neutralist: I think that one important part of philosophy is devoted to the neutral assessment of competing worldviews. In my opinion, the neutral assessment of competing worldviews goes by way of comparing the trade-offs made by those competing worldviews between minimising theoretical commitment and maximising explanatory breadth and depth. While there is no general algorithm for carrying out this assessment, there are some cases where we get a clear verdict. In particular, if the commitments of one worldview are a proper subset of the commitments of a second worldview, and yet there is nowhere that the second worldview has an explanatory advantage over the first, then the first worldview is superior to the second. According to me, neutral philosophical evaluation tells us that my metaphysical naturalist worldview is more theoretically virtuous than—and hence to be preferred to—competing Christian worldviews.

I don’t claim to be able to provide here—or anywhere else—a comprehensive assessment of the comparative theoretical virtues of my metaphysical naturalist worldview and competing Christian worldviews. What I give is a sketch that leaves almost all of the details undiscussed. Moreover, the conclusion that I reach is evidently contentious. Some will wish to reject my philosophical neutralism. (I think that those people go badly wrong; I cannot accept the implicit suggestion that philosophy ought everywhere be the mouthpiece of dogmatism.) Others will contest the details of my assessment. That seems fair to me: there are many controversial matters for judgment that feed into final verdicts about which worldviews are more theoretically virtuous than other competing worldviews.

It is worth noting that I do not say that there is conflict between Christianity and philosophy. It is perfectly possible to do Christian philosophy, i.e. to work on the philosophical development and improvement of Christian worldviews. My claims is just that, as I see it, the part of philosophy devoted to the neutral assessment of worldviews says that my metaphysical naturalist worldview is superior to competing Christian worldviews.

Among the other contributors to this discussion, it seems to me that only Tim McGrew (“Convergence”) has any sympathy for philosophical neutralism. In his view, the neutral assessment of competing worldviews is best handled in a Bayesian framework. Moreover, in his view, Bayesian deliberation delivers the conclusion that Christianity is to be preferred to metaphysical naturalism. While it is not entirely clear, I think that his use of derivations in the prosecution of his case shows that he thinks that metaphysical naturalism is logically inconsistent. In any case, I maintain that neutral philosophical assessment cannot be Bayesian because there are crippling theoretical problems for Bayesian analysis generated by—for example—the role played by prior probabilities in that framework.

Paul Moser (“Conformation”) rejects philosophical neutralism in favour of a reconceptualization of philosophy in which Christ is the central focus. While I’m happy to allow that philosophers can work on the development and improvement of Christian worldviews, I doubt that Moser’s proposed reconceptualization would benefit either philosophy or Christianity. On the one hand, there is an enormous amount in philosophy to which Christ is simply irrelevant. (For example, whether Christianity is true or false makes no difference whatsoever to the proper philosophical treatment of the two envelope paradox, or the liar paradox, or Zeno’s paradoxes of motion, or a thousand other philosophical topics.) On the other hand, Christianity benefits if there is a part of philosophy that provides a neutral standpoint from which it can be assessed: in particular, it is much more likely that improvements to Christian worldviews will emerge from criticism that is not committed to Christian worldview.

Scott Oliphant (“Covenant”) claims that philosophical neutralism is simply incoherent: in his opinion, all coherent worldviews presuppose the truth of Christianity. I think that it is obvious that my metaphysical neutralism does not presuppose Christianity; rather, in my view, it (a) entails that Christianity is necessarily false; and (b) trumps Christianity in a properly conducted assessment of theoretical virtue. I do not think that there is any coherent understanding of “presupposition” on which it is the case that worldviews have presuppositions. In particular, it seems to me that we should think of worldviews as maximal consistent theories. But, in any maximal consistent theory, for any proposition that p, exactly one of p and not-p belongs to that theory. While this way of thinking about worldviews is clearly an idealisation, it nonetheless forecloses the possibility that worldviews have presuppositions.

Obviously enough, there is lots of work to be done to build on and improve the position that I have begun to sketch.

First, there is much to be done to flesh out the account of worldviews and the details of the process to be followed in giving a neutral assessment of worldviews. In particular, it is worth noting that the account of worlds and their assessment involves a large amount of idealisation: there are many questions to ask about the relationship between worldview beliefs and the ideal structures that I have discussed.

Second, there is a huge amount of work required to make my metaphysical naturalist worldview and competing Christian worldviews more explicit (and there is also the potentially endless task of constructing better versions of these worldviews). I think that the task of setting out—and comparing—the commitments of worldviews is the most important but also the most difficult philosophical project.

Third, there is the enormous task of filling out all of the detail that feeds into the determination of the comparative theoretical virtue of my metaphysical naturalist worldview and competing Christian worldviews. (I have made a start on this work elsewhere; see, for example, my 2013 book The Best Argument against God (Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan), and my 2015 paper “What Derivations Cannot Do” (Religious Studies 51, 3, 323-34). But most of the work remains to be done).