On June 17th this summer my wife and I flew to Asheville, North Carolina, rented a car, and drove to eastern Tennessee to visit a sister I hadn’t seen for a while. The day before, my best friend in Lynchburg, where I’d lived for fourteen years, saw on Facebook that we were coming east. “Too bad you can’t swing this way,” he wrote. I agreed. Unfortunately, it had to be a quick trip, in Friday, out Monday. “But we’ll have to find a way to see each other soon,” I added, to which he replied, “Yup.”

And that was Mark Wesley Foreman’s last word to me—at least for now. The next morning his remarkable earthly pilgrimage came to an end. He died at home in his study at the age of 67. He passed quickly, no goodbye possible, but his wife of 43 years, Chris, and three daughters—Erin Foreman, Lindsay Leonard (Steven), and Kelly Croucher (Jordan)—knew Mark loved them with all his heart. He had told them many times, and they him.

Their loss is incalculable and still fresh, and they could use our continuing prayers. Likewise his grandchildren Cole, Isaac, Thomas, Penelope, and Joey; and his brothers: David (Sandra), Michael (Louise), Dana (Lisa), and Stuart (Phyllis). Born on December 18, 1954, in Lancaster, California, Mark was son of the late Donald E. Foreman and Carol A. Foreman. In addition to his parents, he was preceded in death by his brothers, Scott Foreman, Paul Foreman, and Patrick “Flip” Foreman.

A humble man of prodigious accomplishments, Mark was a well-known Professor of Philosophy at Liberty University for over 33 years. He earned his Bachelor’s Degree in Music at Westminster Choir College, an achievement near and dear to his heart. Another proud milestone was earning his PhD from the University of Virginia. Mark was extremely active in community theatre, having appeared in or directed over 50 productions. Most notable were his performances as Benjamin Franklin in 1776 and Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, both roles he was born to play. He was associated with Lynchburg Fine Arts Center, Cherry Tree Players, Little Town Players, Commerce Street Theater, Wolfbane Productions, Renaissance Theatre, and Endstation Theater, where his Christian witness was always winsome, attractive, and faithful.

With crystal clarity and fluid erudition that reflected his teaching gifts, musical timing, and knack for narrative, he was also an accomplished author. He published four books, including Prelude to Philosophy: An Introduction for Christians; How Do We Know? An Introduction to Epistemology (with Jamie Dew); and (with his daughter Lindsay) Christianity and Modern Medicine: Foundations for Bioethics. A staple of the Evangelical Philosophical Society, Mark read dozens of papers through the years, joyfully occupied several leadership positions, and encouraged and affirmed so many in attendance, including my Worldview Bulletin colleague Paul Copan.

Paul shared this story about Mark: “I always appreciated Mark’s warmth and kindness over the years. For some reason, he attended any EPS session at which I presented at our annual meeting. He was always so kind in distributing my handouts to everyone in the room, though he confessed, ‘Actually, you think I’m being a servant, but it’s somewhat self-serving because doing this guarantees I get a handout in the event there are more people than handouts!’”

Among all of his accomplishments, his most prized titles were Husband, Dad, and Grandpa. Mark was completely devoted to his wife and children and cherished the time they spent together, especially during their many travels nationally and internationally (always including a Disney trip!). He loved spending time with his girls, and he considered no work more important than loving them well.

It’s a little surprising that Mark and I grew to be so close. In several ways we were opposites. He was everything I wasn’t: gregarious, ebullient, and the life of every party. He knew magic and music and movies and mischief, and somehow his infectious laughter and extroversion and my chronic introversion dovetailed, and he became a kindred spirit, more of a brother than mere friend. Three months after losing him, and I remain gutted, like so many others, yet thankful we need not mourn as those without hope and that Jesus has effected the death of death.

One summer several years back, my wife, stepson, and I were in Eaton Rapids, Michigan, and we knew Mark was planning a visit to Chicago. So we scheduled a get-together there. We drove the three hours or so in order to share a meal with him on the Gold Coast. At the time it seemed like the perfectly natural thing to do, even though, I suppose, it would have been considerably easier to see him by walking across the hall from my office to his. No regrets.

In the weeks before his death, Mark and I chatted on Facebook numerous times. He reflected about his retirement just weeks before. (Adding in his high school teaching, he taught for forty years—a biblical generation.) In our last Messenger exchange this was his final entry:

I have mixed feelings about retiring. Part of me is looking forward to not having to deal with the hassle aspect of it all: all the little hoops admin makes you jump through, students complaining about grades, etc.; but part of me is going to really miss being in the classroom. Interacting with students, helping them to see alternatives and deeper truths. I loved being a teacher. It was who I was. And now that person is gone. I will really feel it come August when everyone is going back to school and I am not. I loved my summers off but come August I always had that itch to get back and going back scratched that itch. Don’t know what will scratch it this fall.

I suspect he’s not disappointed.

After we heard the news while in Tennessee, Marybeth and I decided to take leave of my sister and drive to Lynchburg the next morning. That evening we attended a hastily arranged dinner with the old philosophy and theology department from Liberty at La Villa, the same restaurant Mark and I usually ate at on Monday evenings. For years I’d order the “Katy Special,” and did so again this night. About twenty showed up. Several brought their wives, and Mark Foreman’s wife Chris and daughter Lindsay came as well (and two of Lindsay’s kids). It was a poignant, bittersweet time of rekindling old friendships, catching up, and celebrating Mark.

We went around the circle and reminisced. I told the story of how Gary Habermas was once discussing near death experiences, and Mark quipped, “I have a near death experience every time I hear you give a paper.” And how another time I overheard Mark discussing Viagra with some fellows when he said, “If mine lasts more than four hours, I’m not just telling my doctor, I’m telling everybody!”

Mark was a marvel, and losing him was devastating and surreal. This was the guy who sang three times at my wedding and reception. Decked out in a classy tuxedo, he and his friend Sally Southall sang “The Prayer” during the wedding itself. Afterwards, simply because I asked him to, he put on a dress and did a Marilyn Monroe impression singing Happy Birthday to my dean, Emily Heady. Then, on his own initiative, he donned a different dress and wig to impersonate Karen Swallow Prior singing his own version of “Matchmaker.” Anyone who knows him will know he brought the proverbial house down. And he left us with a few priceless images seared into our brains forevermore.

Together he and I saw John McEnroe play tennis in person; we attended Phantom of the Opera in London; we toured Oxford University; we saw Shakespeare plays together in Staunton. He organized my bachelor party at the local ballpark; with friends we walked the streets of Washington, D.C. while he regaled us with tales of Watergate. I attended his dissertation defense—he had written on Gilbert Meilaender and the relevance of religious convictions in the public square. He, his family, and I shared Thanksgiving and Christmas meals more times than I remember. And for nearly fourteen years, every Monday night, we watched the most violent film playing that week after dining and talking at length over Italian food.

We shared so many conversations through the years that in retrospect they easily blend, but their cumulative effect over the years was considerable. We had occasion to discuss just about anything and everything under the sun. Including death, quite a number of times. He was the one who’d told me Robin Williams had died, and after Jerry Falwell, Sr. died, we sat in Macado’s and decompressed and processed it all for hours. Once I remember him saying, “I know some people say they want their funerals to be celebrations. I do not. I want there to be tears and wailing.”

In a sense our weekly pilgrimage constituted our shared ritual, something we came to rely on and that invariably shaped us. It really was a liturgy of sorts. Christians have always taught that there is something deeply sacramental in a shared meal, a vivid example of how we can catch a glimpse of the eternal in the everyday, the transcendent in the immanent, something sacred in the quotidian.

Mourning makes me thankful for Romans 8:26: “In the same way the Spirit also helps our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we should, but the Spirit Himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words.”

The loss of a dear friend like Mark is a poignant reminder of the value of people, in general, by reminding us of the value of this person in all his particularity and uniqueness. What a remarkable life Mark lived, and how exceedingly valuable he was as a human being. And of course he’s not alone. Each and every person has infinite value and dignity and worth. In “The Weight of Glory,” C. S. Lewis wrote, “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal…. It is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.” It’s just that Mark made this eminently easy to believe.

We’ll see Mark’s wife and daughter Lindsay again soon as they are planning to rent a truck and drive his remaining book collection here to Houston Baptist so the Center for the Foundations of Ethics can have them. I’m eager to see them and reminisce in person. And I can hardly wait to see Mark again, which is possible because the gospel really is gloriously good news, because God is a God of perfect love, and because love is more powerful than death.

And he already told me the first thing he’ll say when we meet again: “Let’s eat.”

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that memorial contributions be made in Mark’s name to Little Town Players, 931 Ashland Ave, Bedford VA 24523, or Commerce Street Theater, 1022 Commerce Street, Lynchburg, VA, 24504.

To hear Mark’s inimitable voice, here’s a song he sang in 1989.

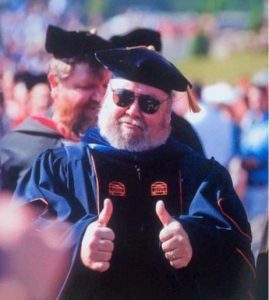

A picture of Foreman looking awesome (and me awkward):